Policy Changes in the EU Complicate Sweden’s Efforts to Rescue Dawit Isaak

Regional challenges and the EU’s enhanced focus on curbing irregular African migration has led to a growing reluctance to press Eritrea on serious human rights violations.

Sweden and the EU must draw a sharp line to show that they are willing to do two things at once – work effectively with European and international partners on projects of common interest, but also vigorously protect their citizens and forcefully advocate on their behalf. This latter aspect is clearly missing.

In addition, the Swedish government’s refusal to share details about Mr. Isaak’s case makes it difficult for EU and other international diplomats to create an effective advocacy strategy.

An abbreviated version of this article “Varför tillåts Eritrea kränka mänskliga rättigheter utan konsekvenser?” (Why is Eritrea permitted to commit human rights violations without consequence?) was published in

Suanne Berger Caroline Edelstam

June 17, 2025

“Human rights, including freedom of expression, are a cornerstone of liberal democracy. The Government will continue its efforts to secure the release of journalist Dawit Isaak.”

This was Swedish Prime Minister Ulf Kristersson’s most recent government statement in September 2024, concerning the continued imprisonment of Swedish Eritrean journalist Dawit Isaak in Eritrea.

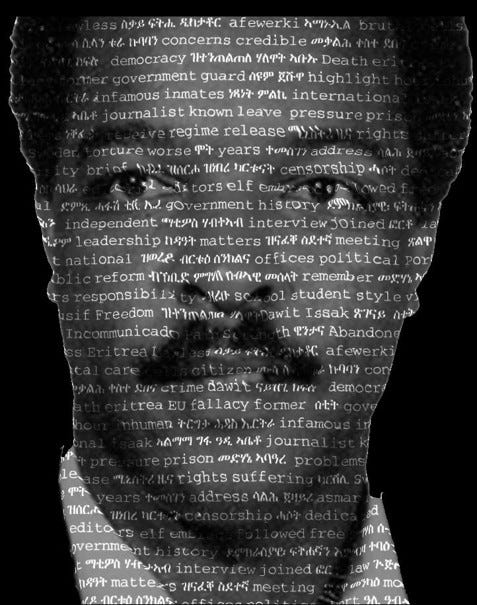

Since 2001, five Prime Ministers and eight Swedish Foreign Ministers have repeated the very same words as their mantra. What these past and present efforts actually entail nobody really knows. Swedish officials steadfastly refuse to reveal what actions they have taken to free Dawit Isaak who has languished in Eritrean prisons for more than twenty-three years without a formal charge or trial. He is currently the longest imprisoned journalist in the world. The Swedish government has maintained a strict wall of silence in the case, claiming that any public comments could jeopardize not only Mr. Isaak’s release but also his current situation in prison – potentially subjecting him to further mistreatment or retaliation.

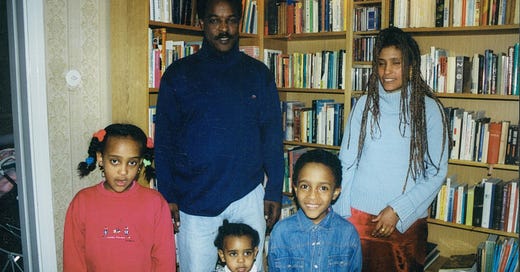

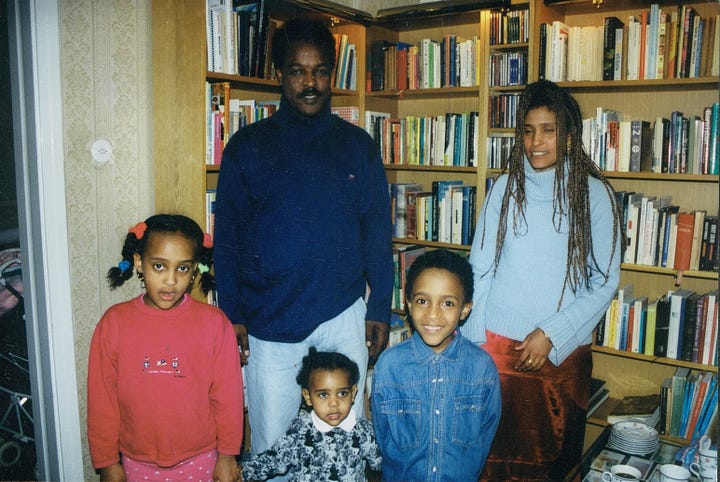

Swedish officials say that in the absence of any clear evidence for Mr. Isaak’s death they presume him to be alive. They have implied in private conversations that they have received strong indications that Mr. Isaak remains imprisoned. However, Sweden has not managed to obtain a formal proof of life from the Eritrean authorities since 2005. At the time, Mr. Isaak was briefly released to seek medical care, only to be immediately rearrested. He has been denied meetings with Swedish diplomats and the International Red Cross. For more than two decades now, he has been held incommunicado, with no contact to the outside world, including his family or his lawyers. His current whereabouts and physical condition are unknown.

Sweden’s official silence impedes international efforts

Mr. Isaak’s family and human rights advocates are especially concerned by the seeming foot dragging and lack of urgency with which Swedish officials have handled Mr. Isaak’s case through the years. They argue that if he is indeed alive, then Sweden must now demonstrate a single-minded focus on securing his release. Unlike in the case of Swedish journalist Joakim Medin who was released last month by Türkiye after being arrested in late March on unsubstantiated terrorism charges, it appears that Mr. Kristersson has not personally intervened with the Eritrean government to facilitate Mr. Isaak’s rescue.

Just as troubling is the Swedish government’s apparent inability or unwillingness to adjust strategy. Family members and activists readily acknowledge the important role of silent diplomacy and behind the scenes negotiations. However, it is becoming increasingly clear that Sweden’ failure to apply any public pressure on the Eritrean regime is undermining its commitment of saving Mr. Isaak.

Both US and EU officials have indicated that the Swedish authorities’ refusal to share important details about his case, especially the question whether he is alive or not, makes it difficult for them to engage and advocate on his behalf. “We presume the crime to be ongoing,” U.S. State Department officials told representatives from the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights (RWCHR) late last year. They added that without clear evidence or at least more detailed information, it is difficult to initiate concrete steps or to recommend actions like the impositions of targeted sanctions on individual members of the regime. In other words, Sweden’s policy of silent diplomacy prevents a more effective engagement from the international community, thereby reducing the chances of freeing Mr. Isaak, who is also an EU citizen

It also means that the Swedish government’s limited international outreach in the Isaak case may prevent it from fully utilizing all available options to aid Mr. Isaak. For example, the U.S. Department of State, in particular the Office of the U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs, recently expanded its mandate to include unlawfully imprisoned or arbitrarily detained citizens of allied nations, an opportunity Sweden appears to be leaving untapped.

Eritrea’s leadership allowed to act with impunity for three decades

The international community’s responsibility and abject failure to hold the Eritrean regime accountable for its egregious human rights violation is baffling, especially since Eritrea is one of the poorest and most repressive regimes in the world. Since 1993, President Isaias Afwerki, a celebrated military leader of Eritrea’s thirty-year struggle for independence (1963-1993), and his close group of advisors have ruled the country with an iron fist. In 2001, while the world’s attention was focused on the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York, Afwerki seized the opportunity to crack down on Eritrea’s internal opposition. He ordered the shutdown of all independent media and imprisoned dozens of government members and journalists who had urged him to adopt democratic reforms.

Eritrea’s mandatory and poorly paid national service has essentially drafted the whole population into forced labor. International human rights organizations have likened the country to an open-air prison.

The Washington Post recently interviewed more than forty former prisoners who testified about the horrific conditions in Eritrean jails. They describe “underground cells of crumbling concrete, and sweltering jails fashioned from converted metal cargo containers,” the article noted. “Cages crammed with hundreds of men who must sleep on their sides like sardines, as their cellmates wearily stand to make room, and shallow holes scraped from the earth with log and dirt ceilings so low that inmates cannot stand up. The conditions, former prisoners recounted, are often so ghastly and the prison terms so open-ended that desperate inmates frequently attempt to escape, but those who try are often gunned down.”

For thirty years now, the Eritrean government has faced near universal condemnation from international entities like the UN Human Rights Council, the UN Rapporteur on Eritrea, the European Parliament, human rights organizations and the Eritrean diaspora. Eritrean opposition groups have documented the Eritrean leadership’s engagement in coercive fundraising operations abroad and its increasing acts of intimidation and transnational repression against Eritrean refugees. Yet, the Eritrean regime continues to violate both domestic and international law with near complete impunity.

The case of Mr. Isaak underscores the point.

In December 2011 Eritrea’s High Court failed to acknowledge a writ of habeas corpus filed by Mr. Isaak’s lawyers. The Eritrean government also ignored a binding ruling by the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights issued in April 2018, which called on Eritrea to immediately release Mr. Isaak and to grant him contact with his family and legal representatives.

In July 2024, in a sharply worded opinion, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention (UNGWAD) called for Mr. Isaak’s “immediate, unconditional release” and referred his case to the Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances and the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment.

Meanwhile, Eritrean officials continue to travel freely, permitted to serve and vote in international forums like the UN and the African Union. Just a few months ago, Sophia Tesfamariam, Eritrea’s Permanent Representative at the UN, was appointed Vice President of UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund.

A notable reluctance to hold Eritrea accountable

Swedish authorities have repeatedly threatened with serious consequences in response to the Eritrean government’s refusal to comply with its demands to immediately free Mr. Isaak. However, so far, the Swedish government has not taken any meaningful steps to hold Eritrean officials accountable for their crimes.

Rather than increasing pressure, both Swedish and EU diplomats are showing a growing reluctance to confront the Eritrean regime in a decisive manner over its dismal human rights record. As a result, President Afwerki seems more firmly ensconced in power than ever before, even as he faces increasing pressure from regime critics abroad.

One reason is the expanding influence of Russia and China with whom Eritrea is closely allied, along with Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Saudi Arabia’s recent $1 billion dollar bid for Eritrea’s Assab port signals not only important financial support for the Eritrean government but a fundamental regional realignment in the Horn of Africa. Eritrea’s geographic location, across from the Arabian Peninsula, with direct port access to the Red Sea, lends it strategic importance with regards to numerous international crises, including the wars in Tigray and Sudan, the war in Gaza, growing tensions with Ethiopia, the fall of the Assad regime in Syria and the continuous threats to international shipping.

The EU’s recent focus on curbing the flow of migration poses additional challenges, with potentially serious implications for the official handling of Mr. Isaak’s case. This past February, Ulf Kristersson announced that Sweden is officially joining the so-called Rome process initiated by Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni in 2023. The highly pragmatic approach - the latest example of the growing influence of geoeconomics (the pursuit of geopolitical policy objectives through economic means) - is supported by more than twenty countries. It is designed to engage African nations with the largest outflow of migrants in the EU to create development projects and a set of policy changes that address the problem at its root. The aim is to engage with African partners on a level of mutual respect, not “exploitation”, as Meloni puts it. All well and good, except that it embraces dictatorships as viable partners, while ignoring or downgrading present day human rights violations. Since 2001, tens of thousands of Eritrean refugees have fled to EU countries, with more than 50,000 Eritreans currently living in Sweden. More than 70,000 reside in Germany.

“Improving repatriation [of refugees] and increasing cooperation with third countries is high on my government's agenda,” Kristersson said in joint press conference with Meloni. “I see the Rome Process as a good example of combining migration and development, trade and economic issues,” he added.

Italy has allocated 6 billion euros for the project, under its Mattei plan; and the EU-Global Gateway Initiative offers 150 billion euros worth of development projects for Africa, with a focus on healthcare, digital technologies, green initiatives and creating sustainable economic growth. Neither initiative appears to set any preconditions or compliance targets for the disbursement of funds, like adherence to international human rights law, protection of civil liberties, including free elections or the release of political prisoners.

A previous agreement between the EU and Tunisia in 2023 was sharply criticized by numerous human rights organizations for bestowing significant financial resources and control of migration to countries guilty of serious human rights violations, including beatings, rape and human trafficking. Some critics have called it "border control disguised as aid.”

It is hard to see Swedish officials imposing punitive measures on the Eritrean regime or vigorously pursuing domestic and international legal actions to end Dawit Isaak’s ordeal, all while seeking Eritrea’s cooperation on key policy issues, including the possible repatriation of some refugees.

Sweden takes punitive measures against Russia but not Eritrea

Unlike Canada, Sweden has taken no steps to stop Eritrea’s imposition of a 2% expatriate tax on Eritreans living in exile. The tax is clearly coercive, with those refusing to pay facing serious repercussions, including fines and even imprisonment of family members back in Eritrea. The Swedish government has also done nothing to restrict travel or residency permits for Eritrean officials and their families.

Over the past ten years, the Swedish Prosecuting Authority (SPA) repeatedly refused to open a criminal investigation in Sweden of members of the Eritrean regime directly involved in Dawit Isaak’s continuing unlawful detention and torture (under the principal of universal jurisdiction). Only yesterday (June 16, 2025) came the news that the SPA rejected yet another appeal filed by Reporters Without Borders.

While agreeing in earlier findings that the crimes committed against Mr. Isaak almost certainly meet the standard of Crimes against Humanity, the Prosecutor General ultimately deferred to concerns voiced by the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs that a criminal inquiry would negatively affect its relations with Eritrea and harm the prospects of securing Mr. Isaak’s release. Critics argued that the decision appears to violate the independence of the judiciary.

In May 2024, in the aftermath of the death of Russian opposition politician Alexei Navalny, Sweden sponsored the creation of a new European sanction framework regarding Russia. This special set of targeted sanctions imposed on Russian officials (including members of the judiciary) were specifically intended to protect activists and civil society groups. When asked, Swedish officials indicated that they have no plans for initiating similar sanction regimes for other autocratic countries like Iran, China or Eritrea, even though Swedish citizens are currently subjected to lengthy arbitrary detentions and enforced disappearances in all three.

Both the US and the EU have imposed targeted sanctions on certain entities and individual members of the Eritrean regime, most notably its notorious National Security Center (led by Brigadier General Abraha Kassa), and General Filipos Woldeyohannes (Filipos), the Chief of Staff of the Eritrean Defense Forces (EDF), for the serious crimes committed against the civilian population in neighboring Tigray (Ethiopia). Nevertheless, other top leaders – including President Afwerki - have not been held accountable. In fact, in January 2024, Afwerki was free to join other African leaders at a summit in Rome, for Italy’s announcement of its new development partnership with African countries. U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s congratulatory statement on the 34th anniversary of Eritrea’s independence did not mention human rights.

Applications by human rights groups to impose targeted sanctions on Eritrea under the EU Global Human Rights Sanctions Regime (GHRSR) have so far failed to advance or even be considered. Similar filings in the UK, Canada and the US have also not yielded any results, with officials expressing reluctance to sanctioning President Afwerki, as head of state - a rationale that effectively protects one of the world’s most repressive leaders from any form of accountability.

There are currently few options of holding President Afwerki accountable. The UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea has recommended the referral of Eritrea to the International Criminal Court (ICC). However, Eritrea is not a member of the Rome Statute, the treaty that established the court. Therefore, any referral would have to be ordered by the UN Security Council, a highly unlikely scenario, with China and Russia expected to exert their veto power.

It is time for Sweden and the EU to draw a sharp line to show that they are willing to do two things at once – work effectively with European and international partners on projects of common interest, but also vigorously protect their citizens and forcefully advocate on their behalf. This latter aspect is clearly missing.

The EU needs to urgently create a joint, closely coordinated advocacy mechanism that sends a strong signal to the world that abuses like the ones suffered by Dawit Isaak will not be tolerated. More than 50 EU citizens are currently known to be arbitrarily detained abroad, although the real number is believed to be much higher.

In the meantime, Sweden and the EU should issue a clear ultimatum to Eritrea: Immediately release Dawit Isaak and all political prisoners, comply with international law or face serious consequences.

#Eritrea #DawitIsaak #humanrights #freedomofexpression #Sweden #EdelstamPrize

Susanne Berger is a Senior Fellow with the Raoul Wallenberg Centre for Human Rights (RWCHR)

Caroline Edelstam is the Co-Founder and President of the Edelstam Foundation